Alpha Geometry: Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations.

Summary:

AlphaGeometry is an AI system developed by DeepMind that can solve complex geometry problems. It uses a combination of a neural language model and a symbolic deduction engine to solve problems. It was able to solve 25 out of 30 Olympiad geometry problems, which is between the average score of human silver and gold medalists.

The system was able to achieve this by generating a large amount of synthetic training data. This data consisted of millions of geometry problems and their solutions. AlphaGeometry was then trained on this data, and it was able to learn to solve new problems by analogy.

AlphaGeometry is a significant advance in the field of artificial intelligence. It shows that AI systems can now be used to solve complex problems that were previously thought to be the exclusive domain of humans.

Here are some of the key takeaways from the paper:

Key takeaways:

AlphaGeometry is a system that can solve geometry problems without any human demonstrations. It does this by using a combination of a symbolic solver and a large language model akin to the idea of thinking, fast and slow, one system provides fast, “intuitive” ideas, and the other, more deliberate, rational decision-making.

Because language models excel at identifying general patterns and relationships in data, they can quickly predict potentially useful constructs, but often lack the ability to reason rigorously or explain their decisions

Symbolic deduction engines, on the other hand, are based on formal logic and use clear rules to arrive at conclusions. The symbolic solver can reason about the things that already exist in the problem, but it cannot introduce new things. The language model is used to suggest new things to construct, such as points, lines, or circles.

AlphaGeometry was trained on a dataset of 100 million synthetic data examples.

Humans can learn geometry using a pen and paper, examining diagrams and using existing knowledge to uncover new, more sophisticated geometric properties and relationships. Our synthetic data generation approach emulates this knowledge-building process at scale, allowing us to train AlphaGeometry from scratch, without any human demonstrations.

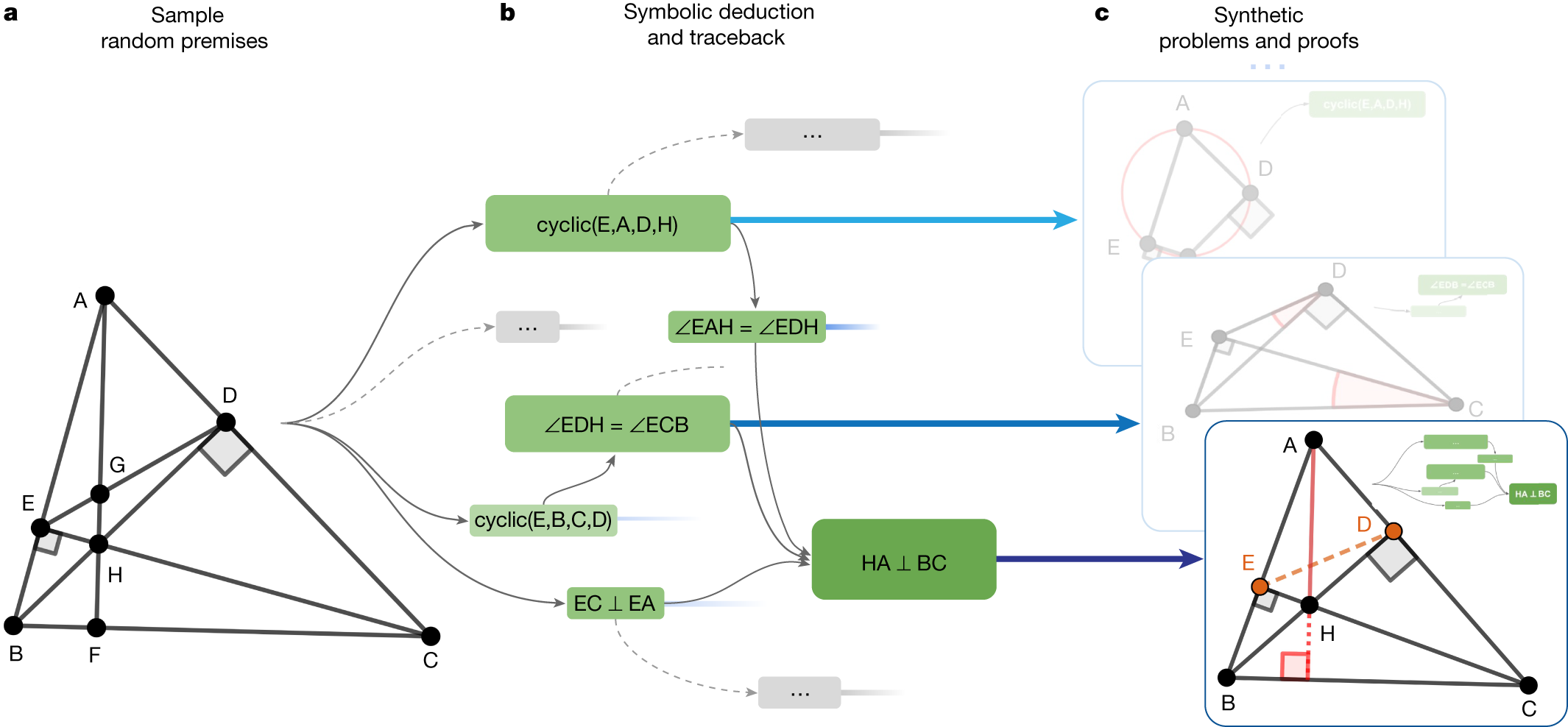

The system starts by generating one billion random diagrams of geometric objects and exhaustively derived all the relationships between the points and lines in each diagram. Then it finds all the proofs contained in each diagram, then works backwards to find out what additional constructs, if any, were needed to arrive at those proofs. We call this process symbolic deduction and traceback.

The system works by first trying to solve the problem with the things that are already there. If it can’t solve the problem, it asks the language model for a suggestion. It then adds the suggestion to the problem and tries to solve it again. This process repeats until the problem is solved.

AlphaGeometry’s solutions have machine-verifiable structure. Yet despite this, its output is still human-readable.

One could have imagined a computer program that solved geometry problems by brute-force coordinate systems: think pages and pages of tedious algebra calculation. AlphaGeometry is not that. It uses classical geometry rules with angles and similar triangles just as students do.”

AlphaGeometry is a very specialized system that only works for a certain type of geometry problem. However, it is very good at solving these problems, and it is often better than humans.

Ablations and Main results

Key innovations:

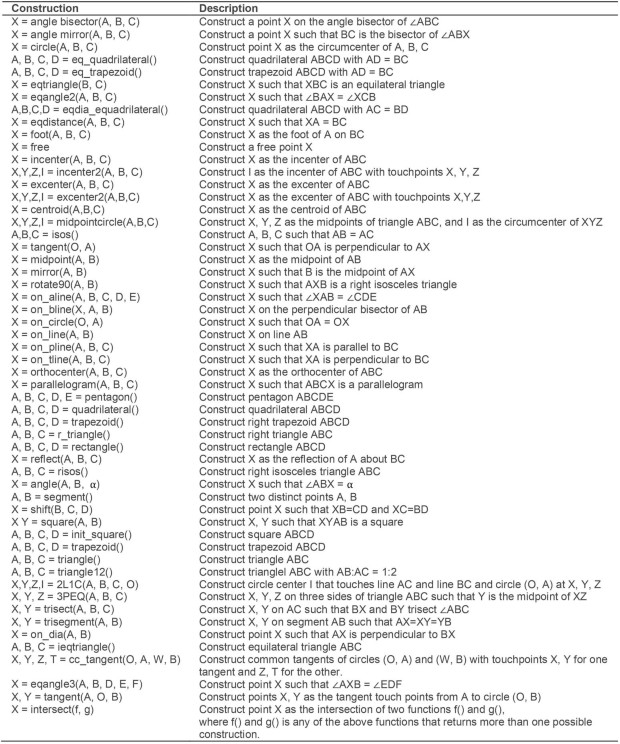

- Synthetic theorems and proofs generation:

- sample a random set of theorem premises based on the following primitives. It constructs one object in the premise at a time, instead of freely sampling many premises that involve several objects, therefore avoiding the generation of a self-contradicting set of premises

These actions include constructions to create new points that are related to others in a certain way, that is, collinear, incentre/excentre etc., as well as constructions that take a number as its parameter, for example, “construct point X such that given a number α, ∠ABX = α”.

One can extend this list with more sophisticated actions to describe a more expressive set of geometric scenarios, improving both the synthetic data diversity and the test-set coverage

- From the initial sampled premises, the symbolic deduction engine obtains a deduction closure.

- This returns a directed acyclic graph of statements. For each node in the graph, we perform traceback to find its minimal set of necessary premise and dependency deductions.

- For example, for the rightmost node “HA ⊥ BC”, traceback returns the green subgraph.

- The minimal premise and the corresponding subgraph constitute a synthetic problem and its solution.

In the bottom example, points E and D took part in the proof despite being irrelevant to the construction of HA and BC; therefore, they are learned by the language model as auxiliary constructions.

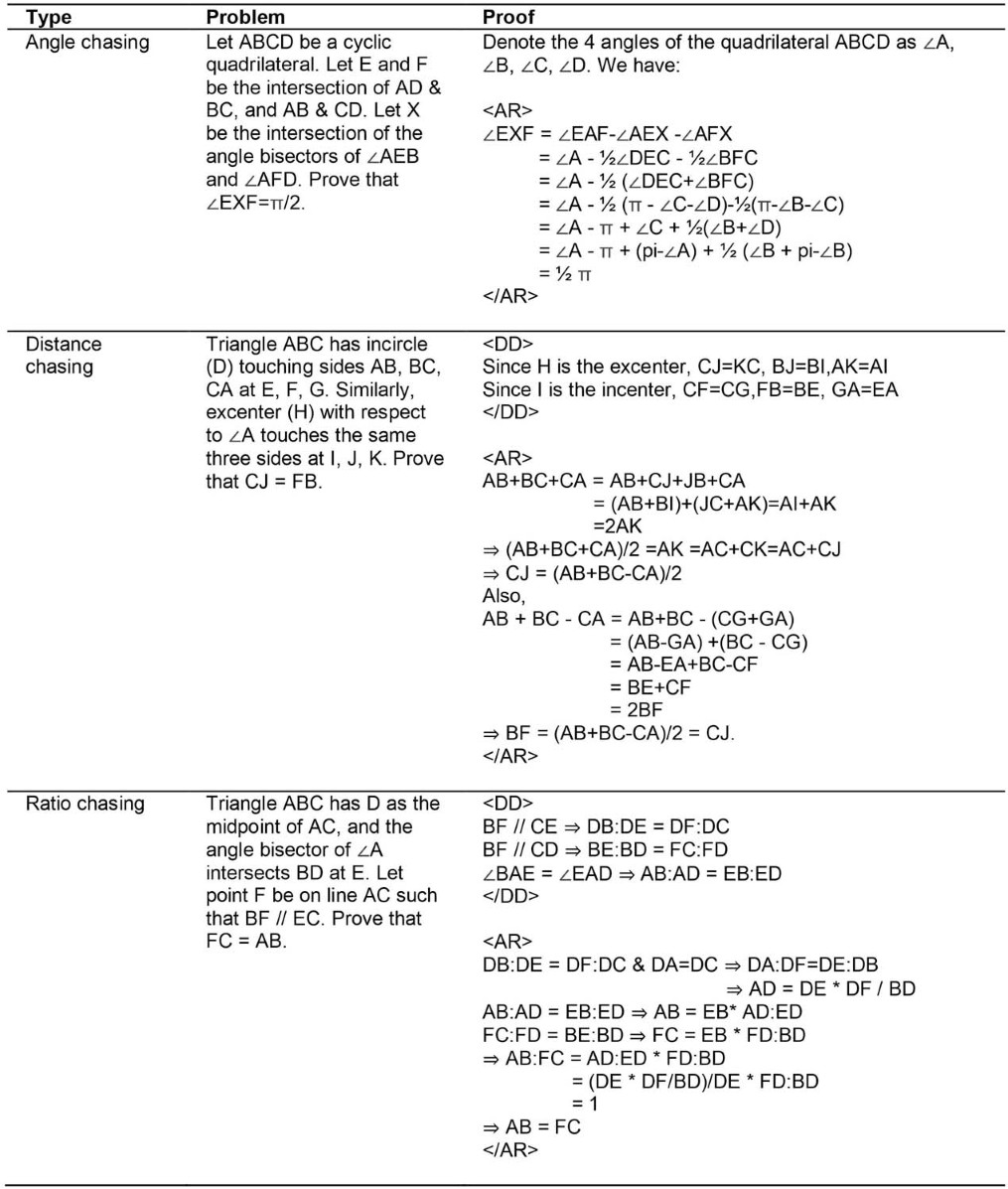

- To widen the scope of the generated synthetic theorems and proofs, we also introduce another component to the symbolic engine that can deduce new statements through algebraic rules (AR)

- Language model trained on synthetic data: The LLM is trained on a dataset of proofs that have been generated by the symbolic solver. This allows the LLM to learn how to generate proofs that are similar to the ones that it has seen before.

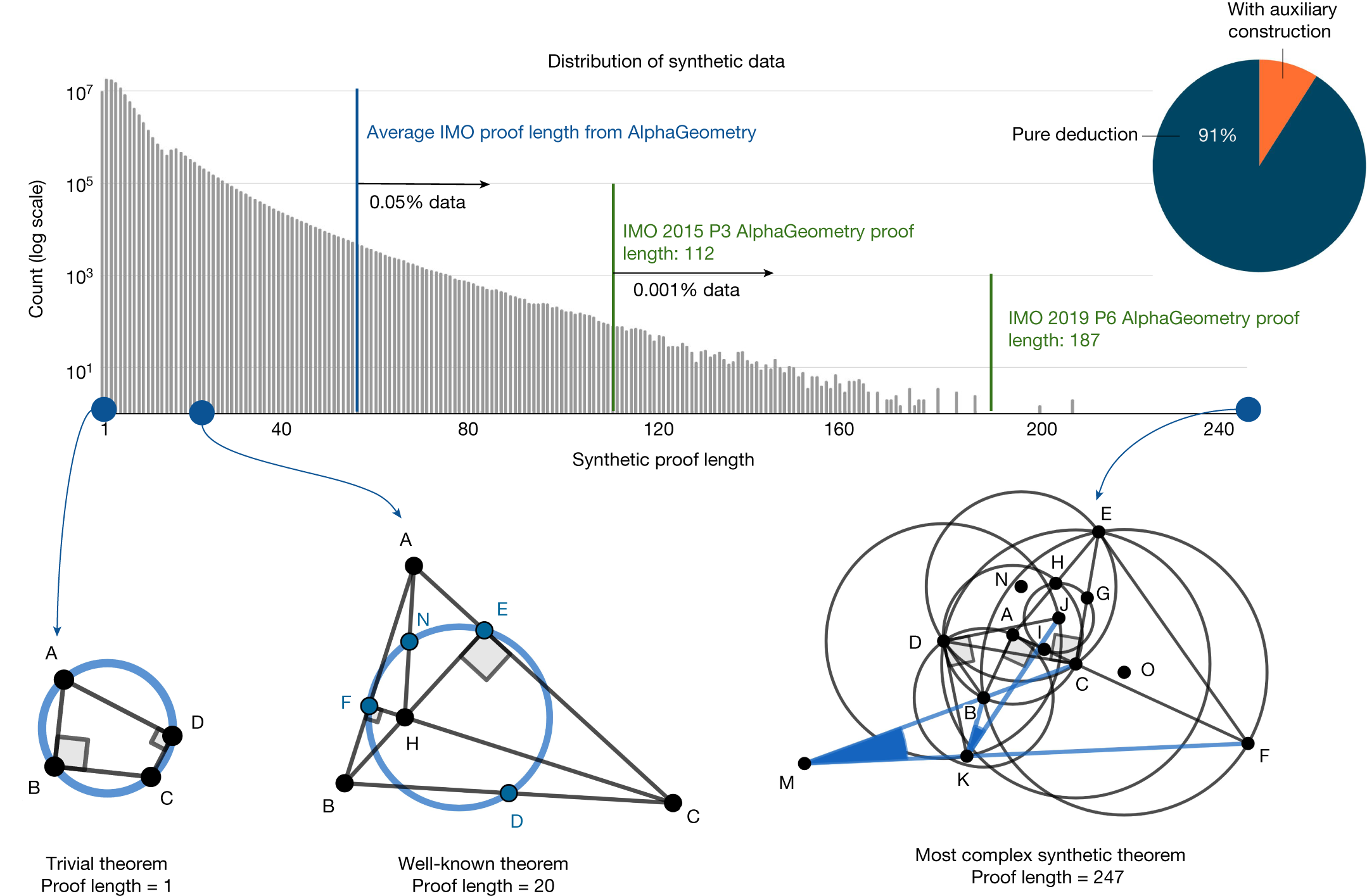

Of the generated synthetic proofs, 9% are with auxiliary constructions. Only roughly 0.05% of the synthetic training proofs are longer than the average AlphaGeometry proof for the test-set problems.

The most complex synthetic proof has an impressive length of 247 with two auxiliary constructions. Most synthetic theorem premises tend not to be symmetrical like human-discovered theorems, as they are not biased towards any aesthetic standard.

Focus on auxiliary constructions: The LLM is specifically trained to suggest new constructions that can be used to prove the problem. This is a key challenge in geometry problem solving, as it is often necessary to introduce new points, lines, or circles in order to prove a theorem.

Interpretable proofs: The proofs generated by the system are written in a natural language that is easy for humans to understand. This is important for debugging and verifying the proofs.

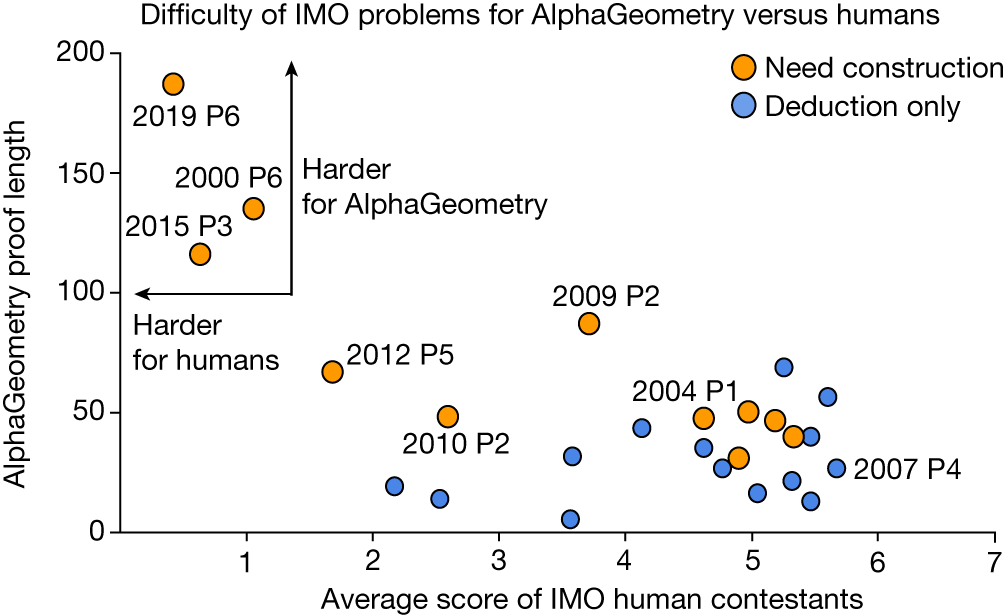

- Hard problems are reflected in AlphaGeometry proof length

Other points:

AlphaGeometry can only solve problems that can be expressed in its limited - language. Additionally, AlphaGeometry is not always able to find the shortest or most elegant proof.

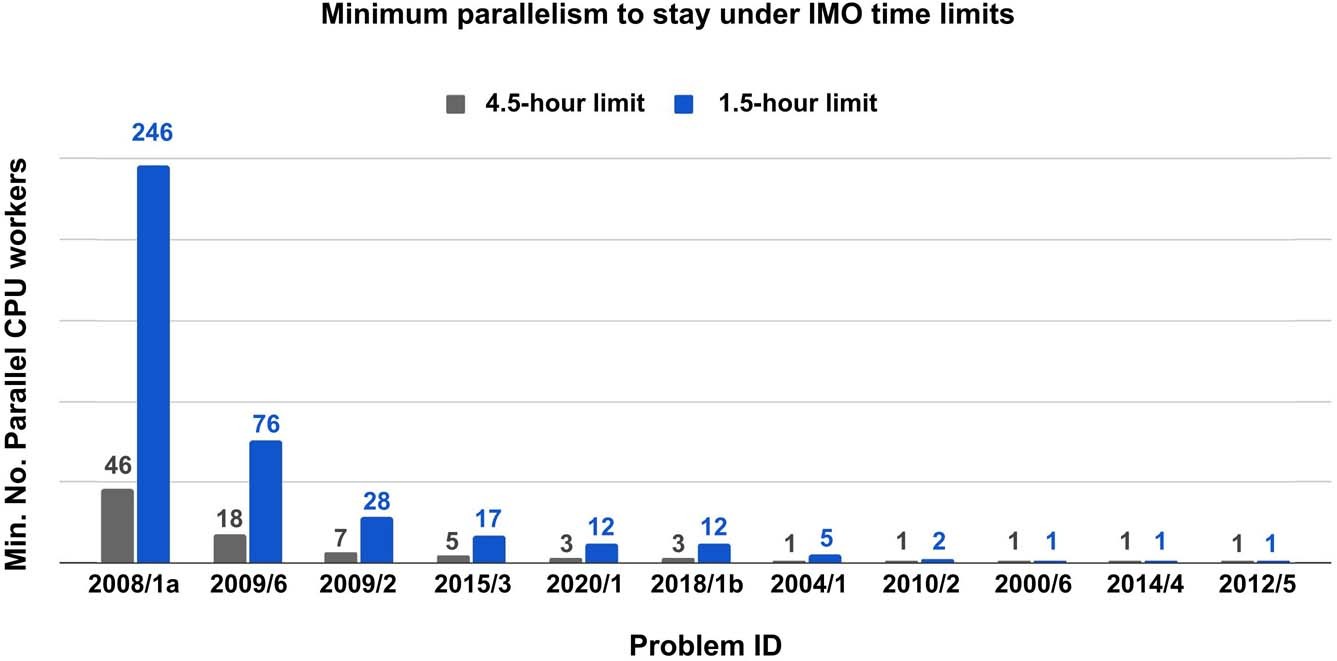

The minimum number of parallel CPU workers to solve all 25 problems and stay under the time limit, given four parallel copies of the GPU V100-accelerated language mode

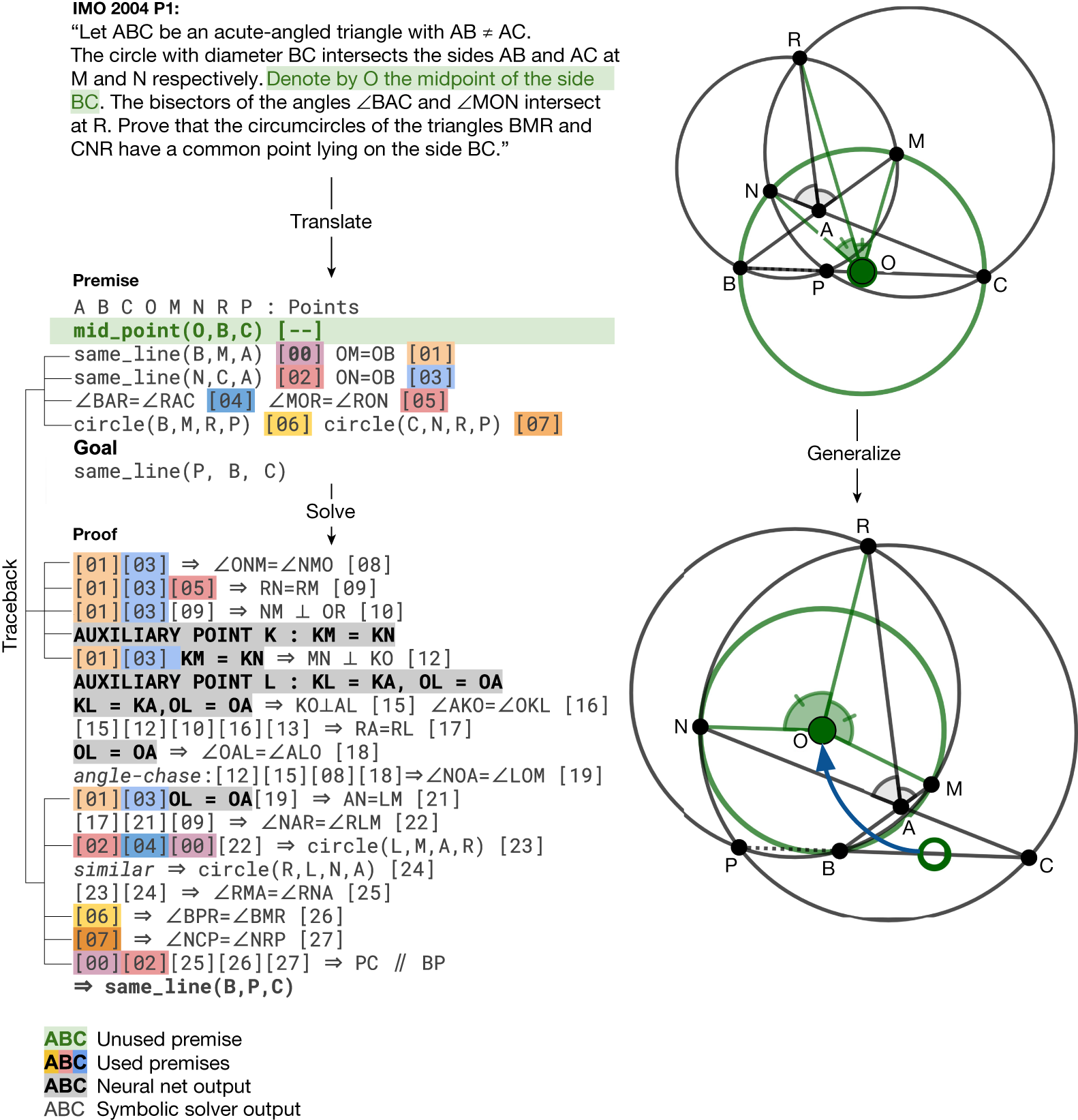

- AlphaGeometry discovers a more general theorem than the translated IMO 2004 P1

- Analysis of AlphaGeometry performance under changes made to its training and testing

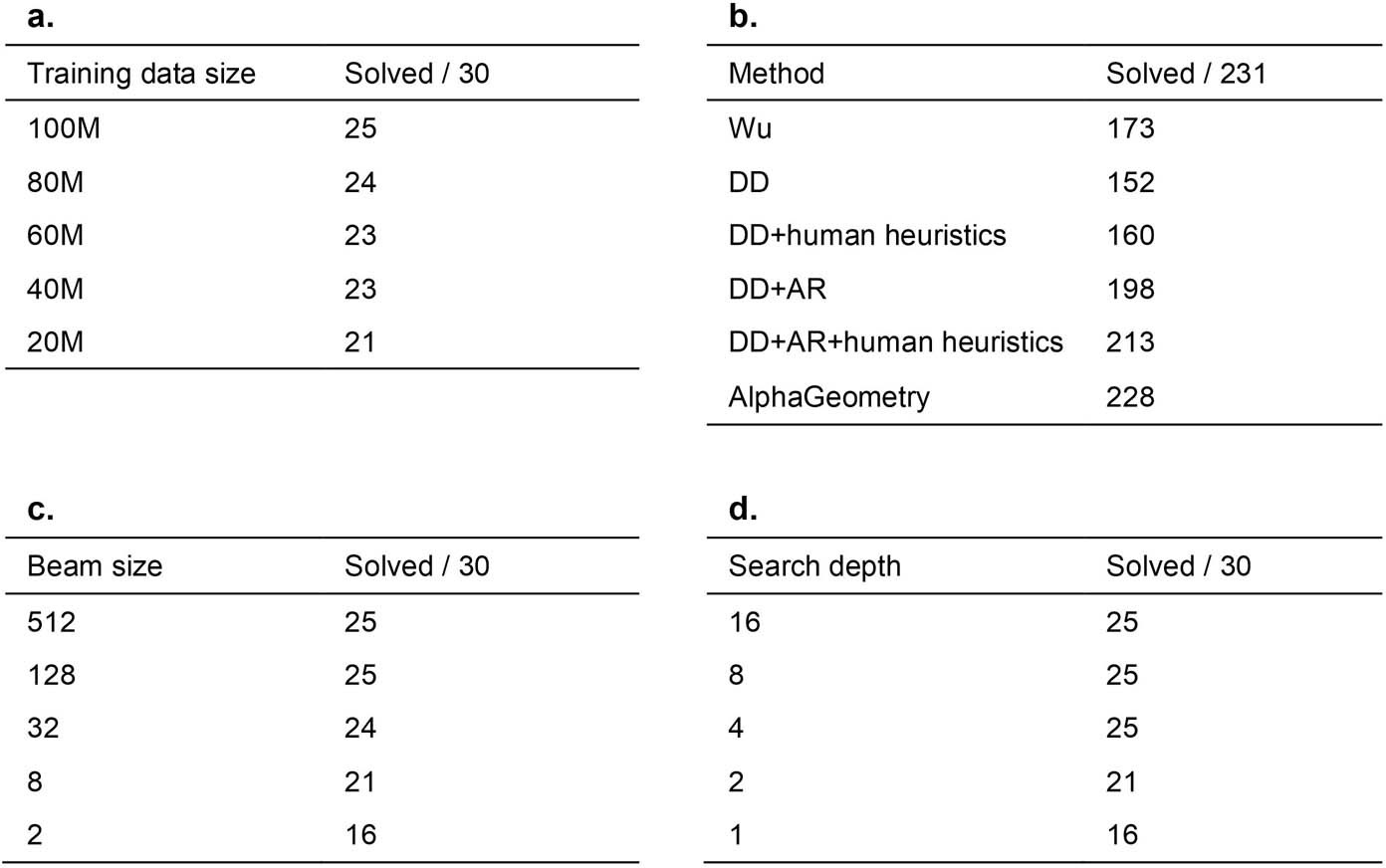

a, The effect of reducing training data on AlphaGeometry performance. At 20% of training data, AlphaGeometry still solves 21 problems, outperforming all other baselines. b, Evaluation on a larger set of 231 geometry problems, covering a diverse range of sources outside IMO competitions. The rankings of different machine solvers stays the same as in Table 1, with AlphaGeometry solving almost all problems. c, The effect of reducing beam size during test time on AlphaGeometry performance. At beam size 8, that is, a 64 times reduction from its full setting, AlphaGeometry still solves 21 problems, outperforming all other baselines. d, The effect of reducing search depth on AlphaGeometry performance. At depth 2, AlphaGeometry still solves 21 problems, outperforming all other baselines.

- Language model architecture and training

- Meliad library for transformer training with its base settings.

- The transformer has 12 layers, embedding dimension of 1,024, eight heads of attention and an inter-attention dense layer of dimension 4,096 with ReLU activation.

- Overall, the transformer has 151 million parameters, excluding embedding layers at its input and output heads.

- Our customized tokenizer is trained with ‘word’ mode using SentencePiece and has a vocabulary size of 757.

- We limit the maximum context length to 1,024 tokens and use T5-style relative position embedding.

- Sequence packing is also used because more than 90% of our sequences are under 200 in length.

- During training, a dropout rate of 5% is applied pre-attention and post-dense.

- A 4 × 4 slice of TPUv3 (ref. 41) is used as its hardware accelerator.

- For pretraining, we train the transformer with a batch size of 16 per core and a cosine learning-rate schedule that decays from 0.01 to 0.001 in 10,000,000 steps.

- For fine-tuning, we maintain the final learning rate of 0.001 for another 1,000,000 steps. For the set-up with no pretraining, we decay the learning rate from 0.01 to 0.001 in 1,000,000 steps. We do not perform any hyperparameter tuning. These hyperparameter values are either selected to be a large round number (training steps) or are provided by default in the Meliad codebase.

Neural Symbolic Solvers (NSSs)

- Neural Symbolic Solvers (NSSs) combine the strengths of neural networks (flexible learning, pattern recognition) with symbolic reasoning (logical inference, interpretability). They aim to address complex tasks that require both robust feature learning and structured reasoning.

Key Components:

Neural Network Component: Typically a deep neural network (DNN) trained on large datasets. Extracts relevant features and patterns from input data. Represents knowledge in a continuous, distributed manner.

- Symbolic Reasoning Component:

- Employs symbolic representations (logic, rules, graphs).

- Performs logical inference, reasoning, and knowledge manipulation.

- Enables interpretability and explainability.

- Integration Approaches:

- Loose Coupling: Neural network and symbolic reasoner interact as separate modules, exchanging information through shared representations or intermediate results.

- Tight Integration: Neural network components are embedded within the symbolic reasoning process, directly influencing reasoning steps.